Neil C Hughes Popular Books

Neil C Hughes Biography & Facts

Currency war, also known as competitive devaluations, is a condition in international affairs where countries seek to gain a trade advantage over other countries by causing the exchange rate of their currency to fall in relation to other currencies. As the exchange rate of a country's currency falls, exports become more competitive in other countries, and imports into the country become more and more expensive. Both effects benefit the domestic industry, and thus employment, which receives a boost in demand from both domestic and foreign markets. However, the price increases for import goods (as well as in the cost of foreign travel) are unpopular as they harm citizens' purchasing power; and when all countries adopt a similar strategy, it can lead to a general decline in international trade, harming all countries. Historically, competitive devaluations have been rare as countries have generally preferred to maintain a high value for their currency. Countries have generally allowed market forces to work, or have participated in systems of managed exchanges rates. An exception occurred when a currency war broke out in the 1930s when countries abandoned the gold standard during the Great Depression and used currency devaluations in an attempt to stimulate their economies. Since this effectively pushes unemployment overseas, trading partners quickly retaliated with their own devaluations. The period is considered to have been an adverse situation for all concerned, as unpredictable changes in exchange rates reduced overall international trade. According to Guido Mantega, former Brazilian Minister for Finance, a global currency war broke out in 2010. This view was echoed by numerous other government officials and financial journalists from around the world. Other senior policy makers and journalists suggested the phrase "currency war" overstated the extent of hostility. With a few exceptions, such as Mantega, even commentators who agreed there had been a currency war in 2010 generally concluded that it had fizzled out by mid-2011. States engaging in possible competitive devaluation since 2010 have used a mix of policy tools, including direct government intervention, the imposition of capital controls, and, indirectly, quantitative easing. While many countries experienced undesirable upward pressure on their exchange rates and took part in the ongoing arguments, the most notable dimension of the 2010–11 episode was the rhetorical conflict between the United States and China over the valuation of the yuan. In January 2013, measures announced by Japan which were expected to devalue its currency sparked concern of a possible second 21st century currency war breaking out, this time with the principal source of tension being not China versus the US, but Japan versus the Eurozone. By late February, concerns of a new outbreak of currency war had been mostly allayed, after the G7 and G20 issued statements committing to avoid competitive devaluation. After the European Central Bank launched a fresh programme of quantitative easing in January 2015, there was once again an intensification of discussion about currency war. Background In the absence of intervention in the foreign exchange market by national government authorities, the exchange rate of a country's currency is determined, in general, by market forces of supply and demand at a point in time. Government authorities may intervene in the market from time to time to achieve specific policy objectives, such as maintaining its balance of trade or to give its exporters a competitive advantage in international trade. Reasons for intentional devaluation Devaluation, with its adverse consequences, has historically rarely been a preferred strategy. According to economist Richard N. Cooper, writing in 1971, a substantial devaluation is one of the most "traumatic" policies a government can adopt – it almost always resulted in cries of outrage and calls for the government to be replaced. Devaluation can lead to a reduction in citizens' standard of living as their purchasing power is reduced both when they buy imports and when they travel abroad. It also can add to inflationary pressure. Devaluation can make interest payments on international debt more expensive if those debts are denominated in a foreign currency, and it can discourage foreign investors. At least until the 21st century, a strong currency was commonly seen as a mark of prestige, while devaluation was associated with weak governments. However, when a country is suffering from high unemployment or wishes to pursue a policy of export-led growth, a lower exchange rate can be seen as advantageous. From the early 1980s the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has proposed devaluation as a potential solution for developing nations that are consistently spending more on imports than they earn on exports. A lower value for the home currency will raise the price for imports while making exports cheaper. This tends to encourage more domestic production, which raises employment and gross domestic product (GDP). Such a positive impact is not guaranteed however, due for example to effects from the Marshall–Lerner condition. Devaluation can be seen as an attractive solution to unemployment when other options, like increased public spending, are ruled out due to high public debt, or when a country has a balance of payments deficit which a devaluation would help correct. A reason for preferring devaluation common among emerging economies is that maintaining a relatively low exchange rate helps them build up foreign exchange reserves, which can protect against future financial crises. Mechanism for devaluation A state wishing to devalue, or at least check the appreciation of its currency, must work within the constraints of the prevailing International monetary system. During the 1930s, countries had relatively more direct control over their exchange rates through the actions of their central banks. Following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, markets substantially increased in influence, with market forces largely setting the exchange rates for an increasing number of countries. However, a state's central bank can still intervene in the markets to effect a devaluation – if it sells its own currency to buy other currencies then this will cause the value of its own currency to fall – a practice common with states that have a managed exchange rate regime. Less directly, quantitative easing (common in 2009 and 2010), tends to lead to a fall in the value of the currency even if the central bank does not directly buy any foreign assets. A third method is for authorities simply to talk down the value of their currency by hinting at future action to discourage speculators from betting on a future rise, though sometimes this has little discernible effect. Finally, a central bank can effect a devaluation by lowering its base rate of interest; however this sometime.... Discover the Neil C Hughes popular books. Find the top 100 most popular Neil C Hughes books.

Best Seller Neil C Hughes Books of 2024

-

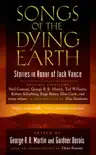

Songs of the Dying Earth

George R.R. Martin & Gardner DozoisThis tribute anthology celebrates the work of SF/F legend Jack Vance, featuring original stories from George R. R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, Dan Simmons, Elizabeth Moon, Tanith Lee, Tad...