Dorothy Parker Marion Meade Popular Books

Dorothy Parker Marion Meade Biography & Facts

Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, writer, critic, wit, and satirist based in New York; she was known for her caustic wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary works published in magazines, such as The New Yorker, and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed when her involvement in left-wing politics resulted in her being placed on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a "wisecracker". Nevertheless, both her literary output and reputation for sharp wit have endured. Some of her works have been set to music. Early life and education Also known as Dot or Dottie, Parker was born Dorothy Rothschild in 1893 to Jacob Henry Rothschild and his wife Eliza Annie (née Marston) (1851–1898) at 732 Ocean Avenue in Long Branch, New Jersey. Parker wrote in her essay "My Home Town" that her parents returned from their summer beach cottage there to their Manhattan apartment shortly after Labor Day (September 4) so that she could be called a true New Yorker. Parker's mother was of Scottish descent. Her father was the son of Sampson Jacob Rothschild (1818–1899) and Mary Greissman (b. 1824), both Prussian-born Jews. Sampson Jacob Rothschild was a merchant who immigrated to the United States around 1846, settling in Monroe County, Alabama. Dorothy's father was one of five known siblings: Simon (1854–1908); Samuel (b. 1857); Hannah (1860–1911), later Mrs. William Henry Theobald; and Martin, born in Manhattan on December 12, 1865, who perished in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Her mother died in Manhattan in July 1898, a month before Parker's fifth birthday. Her father remarried in 1900 to Eleanor Frances Lewis (1851–1903), a Protestant. Parker has been said to have hated her father, who allegedly physically abused her, and her stepmother, whom she is said to have refused to call "mother", "stepmother", or "Eleanor", instead referring to her as "the housekeeper". However, her biographer Marion Meade refers to this account as "largely false", stating that the atmosphere in which Parker grew up was indulgent, affectionate, supportive and generous. Parker grew up on the Upper West Side and attended a Roman Catholic elementary school at the Convent of the Blessed Sacrament on West 79th Street with her sister, Helen, and classmate Mercedes de Acosta. Parker once joked that she was asked to leave following her characterization of the Immaculate Conception as "spontaneous combustion". Her stepmother died in 1903, when Parker was nine. Parker later attended Miss Dana's School, a finishing school in Morristown, New Jersey. She graduated in 1911, at the age of 18, according to Kinney, just before the school closed, although Rhonda Pettit and Marion Meade state she never graduated from high school. Following her father's death in 1913, she played piano at a dancing school to earn a living while she worked on her poetry. She sold her first poem to Vanity Fair magazine in 1914 and some months later was hired as an editorial assistant for Vogue, another Condé Nast magazine. She moved to Vanity Fair as a staff writer after two years at Vogue. In 1917, she met a Wall Street stockbroker, Edwin Pond Parker II (1893–1933) and they married before he left to serve in World War I with the U.S. Army 4th Division. She filed for divorce in 1928. Dorothy retained her married name Parker, though she remarried to Alan Campbell, screenwriter and former actor, in 1934, and moved to Hollywood. Algonquin Round Table years Parker's career took off in 1918 while she was writing theater criticism for Vanity Fair, filling in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met Robert Benchley, who became a close friend, and Robert E. Sherwood. The trio began lunching at the Algonquin Hotel almost daily and became founding members of what became known as the Algonquin Round Table. This numbered among its members the newspaper columnists Franklin P. Adams and Alexander Woollcott, as well as the editor Harold Ross, the novelist Edna Ferber, the reporter Heywood Broun, and the comedian Harpo Marx. Through their publication of her lunchtime remarks and short verses, particularly in Adams' column "The Conning Tower", Parker began developing a national reputation as a wit. Parker's caustic wit as a critic initially proved popular, but she was eventually dismissed by Vanity Fair on January 11, 1920 after her criticisms had too often offended the playwright–producer David Belasco, the actor Billie Burke, the impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, and others. Benchley resigned in protest. (Sherwood is sometimes reported to have done so too, but in fact had been fired in December 1919.) Parker soon started working for Ainslee's Magazine, which had a higher circulation. She also published pieces in Vanity Fair, which was happier to publish her than employ her, The Smart Set, and The American Mercury, but also in the popular Ladies’ Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post, and Life. When Harold Ross founded The New Yorker in 1925, Parker and Benchley were part of a board of editors he established to allay the concerns of his investors. Parker's first piece for the magazine was published in its second issue. She became famous for her short, viciously humorous poems, many highlighting ludicrous aspects of her many (largely unsuccessful) romantic affairs and others wistfully considering the appeal of suicide. The next 15 years were Parker's period of greatest productivity and success. In the 1920s alone she published some 300 poems and free verses in Vanity Fair, Vogue, "The Conning Tower" and The New Yorker as well as Life, McCall's and The New Republic. Her poem "Song in a Minor Key" was published during a candid interview with New York N.E.A. writer Josephine van der Grift. Parker published her first volume of poetry, Enough Rope, in 1926. It sold 47,000 copies and garnered impressive reviews. The Nation described her verse as "caked with a salty humor, rough with splinters of disillusion, and tarred with a bright black authenticity". Although some critics, notably The New York Times' reviewer, dismissed her work as "flapper verse", the book helped Parker's reputation for sparkling wit. She released two more volumes of verse, Sunset Gun (1928) and Death and Taxes (1931), along with the short story collections Laments for the Living (1930) and After Such Pleasures (1933). Not So Deep as a Well (1936) collected much of the material previously published in Rope, Gun, and Death; and she re-released her fiction with a few new pieces in 1939 as Here Lies. Parker collaborated with playwright Elmer Rice to create Close Harmony, which ran on Broadway in December 1924. T.... Discover the Dorothy Parker Marion Meade popular books. Find the top 100 most popular Dorothy Parker Marion Meade books.

Best Seller Dorothy Parker Marion Meade Books of 2024

-

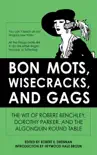

Bon Mots, Wisecracks, and Gags

Robert E. Drennan & Heywood Hale Broun“Stop looking at the world through rosecolored bifocals.” “His mind is so open, the wind whistles through it.” “You can’t teach an old dogma new tricks.” Ever wonder where these sa...