E B White Edmund Ware Smith Popular Books

E B White Edmund Ware Smith Biography & Facts

Pottery and porcelain (陶磁器, tōjiki, also yakimono (焼きもの), or tōgei (陶芸)) is one of the oldest Japanese crafts and art forms, dating back to the Neolithic period. Kilns have produced earthenware, pottery, stoneware, glazed pottery, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and blue-and-white ware. Japan has an exceptionally long and successful history of ceramic production. Earthenwares were made as early as the Jōmon period (10,500–300 BC), giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world. Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics hold within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony. Japanese ceramic history records the names of numerous distinguished ceramists, and some were artist-potters, e.g. Hon'ami Kōetsu, Ogata Kenzan, and Aoki Mokubei. Japanese anagama kilns also have flourished through the ages, and their influence weighs with that of the potters. Another important Japanese constituent of the art is the continuing popularity of unglazed high-fired stoneware even after porcelain became popular. Since the 4th century AD, Japanese ceramics have often been influenced by the artistic sensibilities of neighbouring East Asian civilizations such as Chinese and Korean-style pottery. Japanese ceramists and potters took inspiration from their East Asian artistic counterparts by transforming and translating the Chinese and Korean prototypes into a uniquely Japanese creation, with the resultant form being distinctly Japanese in character. Since the mid-17th century when Japan started to industrialize, high-quality standard wares produced in factories became popular exports to Europe. In the 20th century, a modern homegrown cottage ceramics industry began to take root and emerge, with notable companies such as Noritake and Toto Ltd. having sprung up across the Japanese ceramics landscape. Japanese pottery is distinguished by two polarized aesthetic traditions. On the one hand, there is a tradition of very simple and roughly finished pottery, mostly in earthenware and using a muted palette of earth colours. This relates to Zen Buddhism and many of the greatest masters were priests, especially in early periods. Many pieces are also related to the Japanese tea ceremony and embody the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi. Most raku ware, where the final decoration is partly random, is in this tradition. The other tradition is of highly finished and brightly coloured factory wares, mostly in porcelain, with complex and balanced decoration, which develops Chinese porcelain styles in a distinct way. A third tradition, of simple but perfectly formed and glazed stonewares, also relates more closely to both Chinese and Korean traditions. In the 16th century, a number of styles of traditional utilitarian rustic wares then in production became admired for their simplicity, and their forms have often been kept in production to the present day for a collectors market. History Jōmon period In the Neolithic period (c. 11th millennium BC), the earliest soft earthenware was made. During the early Jōmon period in the 6th millennium BC typical coil-made ware appeared, decorated with hand-impressed rope patterns. Jōmon pottery developed a flamboyant style at its height and was simplified in the later Jōmon period. The pottery was formed by coiling clay ropes and fired in an open fire. Yayoi period In about the 4th–3rd centuries BC Yayoi period, Yayoi pottery appeared which was another style of earthenware characterised by a simple pattern or no pattern. Jōmon, Yayoi, and later Haji ware shared the firing process but had different styles of design. Kofun period In the 3rd to 4th centuries AD, the anagama kiln, a roofed-tunnel kiln on a hillside, and the potter's wheel appeared, brought to Kyushu island from the Korean peninsula. The anagama kiln could produce stoneware, Sue pottery, fired at high temperatures of over 1,200–1,300 °C (2,190–2,370 °F), sometimes embellished with accidents produced when introducing plant material to the kiln during the reduced-oxygen phase of firing. Its manufacture began in the 5th century and continued in outlying areas until the 14th century. Although several regional variations have been identified, Sue was remarkably homogeneous throughout Japan. The function of Sue pottery, however, changed over time: during the Kofun period (AD 300–710) it was primarily funerary ware; during the Nara period (710–94) and the Heian period (794–1185), it became an elite tableware; and finally it was used as a utilitarian ware and for the ritual vessels for Buddhist altars. Contemporary Haji ware and haniwa funerary objects were earthenware like Yayoi. Heian period Although a three-color lead glaze technique was introduced to Japan from the Tang dynasty of China in the 8th century, official kilns produced only simple green lead glaze for temples in the Heian period, around 800–1200. Kamui ware appeared in this time, as well as Atsumi ware and Tokoname ware. Kamakura period Until the 17th century, unglazed stoneware was popular for the heavy-duty daily requirements of a largely agrarian society; funerary jars, storage jars, and a variety of kitchen pots typify the bulk of the production. Some of the kilns improved their technology and are called the "Six Old Kilns": Shigaraki (Shigaraki ware), Tamba, Bizen, Tokoname, Echizen, and Seto. Among these, the Seto kiln in Owari Province (present day Aichi Prefecture) had a glaze technique. According to legend, Katō Shirozaemon Kagemasa (also known as Tōshirō) studied ceramic techniques in China and brought high-fired glazed ceramic to Seto in 1223. The Seto kiln primarily imitated Chinese ceramics as a substitute for the Chinese product. It developed various glazes: ash brown, iron black, feldspar white, and copper green. The wares were so widely used that Seto-mono ("product of Seto") became the generic term for ceramics in Japan. Seto kiln also produced unglazed stoneware. In the late 16th century, many Seto potters fleeing the civil wars moved to Mino Province in the Gifu Prefecture, where they produced glazed pottery: Yellow Seto (Ki-Seto), Shino, Black Seto (Seto-Guro), and Oribe ware. Muromachi period According to chronicles in 1406, the Yongle Emperor (1360–1424) of the Ming dynasty bestowed ten Jian ware bowls from the Song dynasty to the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), who ruled during the Muromachi period. A number of Japanese monks who traveled to monasteries in China also brought pieces back home. As they became valued for tea ceremonies, more pieces were imported from China where they became highly prized goods. Five of these vessels from the southern Song dynasty are so highly valued that they were included by the government in the list of National Treasures of Japan (crafts: others). Jian ware was later produced and further developed as tenmoku and was highly priced during tea ceremonies of this time. Azuchi-Momoyama period From the midd.... Discover the E B White Edmund Ware Smith popular books. Find the top 100 most popular E B White Edmund Ware Smith books.

Best Seller E B White Edmund Ware Smith Books of 2024

-

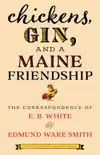

Chickens, Gin, and a Maine Friendship

E. B. White & Edmund Ware SmithDuring the 1950s and ’60s, writers E.B. White and Edmund Ware Smith carried on a long correspondence by letter, despite living only a few miles apart on the coast of Maine. Often t...