Mary H Kingsley Popular Books

Mary H Kingsley Biography & Facts

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (13 October 1862 – 3 June 1900) was an English ethnographer, writer and explorer who made numerous travels through West Africa and wrote several books on her experiences there. Historians have credited Kingsley's work with helping to shape Western perceptions of the culture of Africa and colonialism. Early life Kingsley was born in London on 13 October 1862, the daughter and oldest child of physician, traveller and writer George Kingsley and Mary Bailey. She came from a family of writers, as she was also the niece of novelists Charles Kingsley and Henry Kingsley. The family moved to Highgate less than a year after her birth, the same home where her brother Charles George R. ("Charley") Kingsley was born in 1866, and by 1881 were living in Southwood House, Bexley in Kent. Her father was a physician and worked for George Herbert, 13th Earl of Pembroke and other aristocrats and was frequently away from home on his excursions. During these voyages he collected information for his studies. Dr. Kingsley accompanied Lord Dunraven on a trip to North America from 1870 to 1875. During the trip, Dr. Kingsley was invited to accompany United States Army officer George Armstrong Custer's expedition against the Sioux. The subsequent Battle of the Little Bighorn terrified the Kingsley family, but they were relieved to learn that bad weather had kept Dr. Kingsley from joining Custer. It is possible that her father's views on the brutal treatment of Native Americans in the United States helped shape Mary's later opinions on European colonialism in West Africa. Mary Kingsley had little formal schooling compared to her brother, other than German lessons at a young age; because, at that time and at her level of society, education was not thought to be necessary for a girl. She did, however, have access to her father's large library and loved to hear his stories of foreign countries. She did not enjoy novels that were deemed more appropriate for young ladies of the time, such as those by Jane Austen or Charlotte Brontë, but preferred books on the sciences and memoirs of explorers. In 1886, her brother Charley entered Christ's College, Cambridge, to read law; this allowed Mary to make several academic connections and a few friends. There is little indication that Kingsley was raised Christian; instead, she was a self-proclaimed believer with, "summed up in her own words [...] 'an utter faith in God'" and even identified strongly with what was described as 'the African religion'. She is known for criticizing Christian missionaries and their work for supplanting pre-existing African cultures without proving any material benefits in return. The 1891 England census finds Mary's mother and her two children living at 7 Mortimer Road, Cambridge, where Charles is recorded as a BA Student at Law and Mary as a Student of Medicine. In her later years, Kingsley's mother became ill, and she was expected to care for her well-being. Unable to leave her mother's side, she was limited in her travel opportunities. Soon, her father was also bedridden with rheumatic fever following an excursion. Dr. Kingsley died in February 1892, and Mrs. Kingsley followed a few months later in April of the same year. "Freed" from her family responsibilities and with an inheritance of £8,600 to be split evenly with her brother, Kingsley was now able to travel as she had always dreamed. Adventures to Africa After a preliminary visit to the Canary Islands, Kingsley decided to travel to the west coast of Africa. Generally, the only non-African women who embarked on (often dangerous) journeys to Africa were the wives of missionaries, government officials, or explorers. Exploration and adventure had not been seen as fitting roles for English women, though this was changing under the influence of figures such as Isabella Bird and Marianne North. African women were surprised that a woman of Kingsley's age was travelling without a man, as she was frequently asked why her husband was not accompanying her. Kingsley landed in Sierra Leone on 17 August 1893 and from there travelled further to Luanda in Angola. She lived with local people, who taught her necessary surviving-skills for living in the wilderness, and gave her advice. She often went into dangerous areas alone. Her training as a nurse at the de:Kaiserswerther Diakonie had prepared her for slight injuries and jungle maladies that she would later encounter. Kingsley returned to England in December 1893. Upon her return, Kingsley secured support and aid from Dr. Albert Günther, a prominent zoologist at the British Museum, as well as a writing agreement with publisher George Macmillan, for she wished to publish her travel accounts. She returned to Africa yet again on 23 December 1894 with more support and supplies from England, as well as increased self-assurance in her work. She longed to study "cannibal" people and their traditional religious practices, commonly referred to as "fetish" during the Victorian Era. In April, she became acquainted with Scottish missionary Mary Slessor, another European woman living among native African populations with little company and no husband. It was during her meeting with Slessor that Kingsley first became aware of the custom of twin killing, a custom which Slessor was determined to stop. The native people believed that one of the twins was the offspring of the devil who had secretly mated with the mother and since the innocent child was impossible to distinguish, both were killed and the mother was often killed as well for attracting the devil to impregnate her. Kingsley arrived at Slessor's residence shortly after she had taken in a recent mother of twins and her surviving child. Later in Gabon, Kingsley canoed up the Ogooué River, where she collected specimens of fish previously unknown to western science, three of which were later named after her. After meeting the Fang people and travelling through uncharted Fang territory, she daringly climbed the 4,040 metres (13,250 ft) Mount Cameroon by a route not previously attempted by any other European. She moored her boat at Donguila. Return to England When she returned home in November 1895, Kingsley was greeted by journalists eager to interview her. The reports that were drummed up about her voyage, however, were most upsetting, as the papers portrayed her as a "New Woman", an image which she did not embrace. Kingsley distanced herself from any feminist movement claims, arguing that women's suffrage was "a minor question; while there was a most vital section of men disenfranchised women could wait". Her consistent lack of identification with women's rights movements may be attributed to a number of causes, such as the attempt to ensure that her work would be received more favorably; in fact, some insist this might be a direct reference to her belief in the importance of securing rights for British traders in West Africa. Over the next three years, she toure.... Discover the Mary H Kingsley popular books. Find the top 100 most popular Mary H Kingsley books.

Best Seller Mary H Kingsley Books of 2024

-

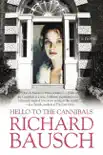

Hello to the Cannibals

Richard BauschAt first, all Lily Austin knows about 19th–century explorer Mary Kingsley is that, 100 years before, she was the first white woman to venture into the heart of Africa. But as Lily ...